Global Warming

Bombshell

A prime piece of evidence linking

human activity to climate change

turns out to be an artifact of poor

mathematics

Richard A. Muller

mirrored from

Technology for Presidents

October 15, 2004

Progress in

science is sometimes made by great discoveries. But science also advances

when we learn that something we believed to be true isn't. When solving a

jigsaw puzzle, the solution can sometimes be stymied by the fact that a wrong

piece has been wedged in a key place.

In the

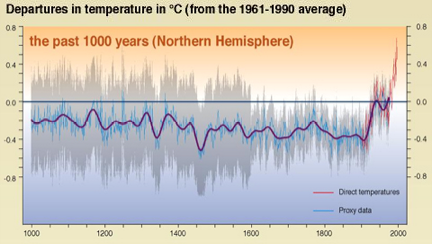

scientific and political debate over global warming, the latest wrong piece may

be the "hockey stick," the famous plot (shown below), published by

University of Massachusetts geoscientist Michael Mann and colleagues. This plot

purports to show that we are now experiencing the warmest climate in a

millennium, and that the earth, after remaining cool for centuries during the

medieval era, suddenly began to heat up about 100 years ago--just at the time

that the burning of coal and oil led to an increase in atmospheric levels of

carbon dioxide.

I talked about

this at length in my December 2003 column. Unfortunately, discussion of this plot

has been so polluted by political and activist frenzy that it is hard to dig

into it to reach the science. My earlier column was largely a plea to let

science proceed unmolested. Unfortunately, the very importance of the issue has

made careful science difficult to pursue.

But now a

shock: Canadian scientists Stephen McIntyre and Ross McKitrick have

uncovered a fundamental mathematical flaw in the computer program that was used

to produce the hockey stick. In his original publications of the stick, Mann

purported to use a standard method known as principal component analysis, or

PCA, to find the dominant features in a set of more than 70 different climate

records.

But it wasn't

so. McIntyre and McKitrick obtained part of the program that Mann used, and

they found serious problems. Not only does the program not do conventional PCA,

but it handles data normalization in a way that can only be described as

mistaken.

Now comes the

real shocker. This improper normalization procedure tends to emphasize any data

that do have the hockey stick shape, and to suppress all data that do not. To

demonstrate this effect, McIntyre and McKitrick created some meaningless test

data that had, on average, no trends. This method of generating random data is

called "Monte Carlo" analysis, after the famous casino, and it is

widely used in statistical analysis to test procedures. When McIntyre and

McKitrick fed these random data into the Mann procedure, out popped a hockey

stick shape!

That discovery

hit me like a bombshell, and I suspect it is having the same effect on many

others. Suddenly the hockey stick, the poster-child of the global warming community,

turns out to be an artifact of poor mathematics. How could it happen? What is

going on? Let me digress into a short technical discussion of how this

incredible error took place.

In PCA and

similar techniques, each of the (in this case, typically 70) different data

sets have their averages subtracted (so they have a mean of zero), and then are

multiplied by a number to make their average variation around that mean to be

equal to one; in technical jargon, we say that each data set is normalized to

zero mean and unit variance. In standard PCA, each data set is normalized over

its complete data period; for key climate data sets that Mann used to create

his hockey stick graph, this was the interval 1400-1980. But the computer

program Mann used did not do that. Instead, it forced each data set to have

zero mean for the time period 1902-1980, and to match the historical records

for this interval. This is the time when the historical temperature is well

known, so this procedure does guarantee the most accurate temperature scale.

But it completely screws up PCA. PCA is mostly concerned with the data sets

that have high variance, and the Mann normalization procedure tends to give

very high variance to any data set with a hockey stick shape. (Such data sets have

zero mean only over the 1902-1980 period, not over the longer 1400-1980

period.)

The net result:

the "principal component" will have a hockey stick shape even if most

of the data do not.

McIntyre and

McKitrick sent their detailed analysis to Nature magazine for publication, and it was

extensively refereed. But their paper was finally rejected. In frustration,

McIntyre and McKitrick put the entire record of their submission and the

referee reports on a Web

page for all to see. If

you look, you'll see that McIntyre and McKitrick have found numerous other

problems with the Mann analysis. I emphasize the bug in their PCA program

simply because it is so blatant and so easy to understand. Apparently, Mann and

his colleagues never tested their program with the standard Monte Carlo

approach, or they would have discovered the error themselves. Other and

different criticisms of the hockey stick are emerging (see, for example, the

paper by Hans von Storch and colleagues in the September 30 issue of Science).

Some people may

complain that McIntyre and McKitrick did not publish their results in a

refereed journal. That is true--but not for lack of trying. Moreover, the paper

was refereed--and even better, the referee reports are there for us to read.

McIntyre and McKitrick's only failure was in not convincing Nature that the paper was important enough to

publish.

How does this

bombshell affect what we think about global warming?

It certainly

does not negate the threat of a long-term global temperature increase. In fact,

McIntyre and McKitrick are careful to point out that it is hard to draw

conclusions from these data, even with their corrections. Did medieval global

warming take place? Last month the consensus was that it did not; now the

correct answer is that nobody really knows. Uncovering errors in the Mann

analysis doesn't settle the debate; it just reopens it. We now know less about

the history of climate, and its natural fluctuations over century-scale time

frames, than we thought we knew.

If you are concerned

about global warming (as I am) and think that human-created carbon dioxide may

contribute (as I do), then you still should agree that we are much better off

having broken the hockey stick. Misinformation can do real harm, because it

distorts predictions. Suppose, for example, that future measurements in the

years 2005-2015 show a clear and distinct global cooling trend. (It could happen.) If we

mistakenly took the hockey stick seriously--that is, if we believed that

natural fluctuations in climate are small--then we might conclude (mistakenly)

that the cooling could not be just a random fluctuation on top of a long-term

warming trend, since according to the hockey stick, such fluctuations are

negligible. And that might lead in turn to the mistaken conclusion that global

warming predictions are a lot of hooey. If, on the other hand, we reject the

hockey stick, and recognize that natural fluctuations can be large, then we

will not be misled by a few years of random cooling.

A phony hockey

stick is more dangerous than a broken one--if we know it is broken. It is our

responsibility as scientists to look at the data in an unbiased way, and draw

whatever conclusions follow. When we discover a mistake, we admit it, learn

from it, and perhaps discover once again the value of caution.

Richard A.

Muller, a 1982 MacArthur Fellow, is a physics professor at the University of

California, Berkeley, where he teaches a course called "Physics for Future

Presidents." Since 1972, he has been a Jason consultant on U.S. national

security.