Medieval Global

Warming

A controversy over 14th century

climate shows the peril of letting politics shape the scientific debate.

By Richard Muller

Technology for Presidents

December 17, 2003

Six hundred years ago, the world was warm. Or maybe it wasn't. What's the truth? Beware. This question has recently been elevated from a mere scientific quandary to one of the hot (or cold) issues of modern politics. Argue in favor of the wrong answer and you risk being branded a liberal alarmist or a conservative Neanderthal. Or you might lose your job.

Six editors

recently resigned from the journal Climate Research because of this issue.

Their crime: publishing the article "Proxy Climatic and Environmental

Changes of the Past 1,000 Years," by W. Soon and S. Baliunas of the

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Without passing

judgment on this particular paper, I can still point out that our journals are

full of poor papers. If editors were dismissed every time they published one,

they would all be out of work within a month or two. What made the Soon and

Baliunas situation different is that their paper attracted enormous attention.

And that's because it threw doubt on the hockey stick.

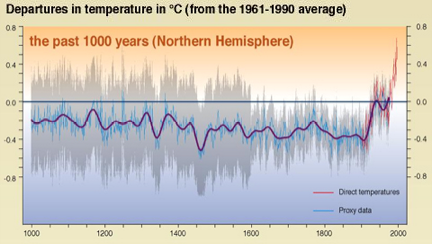

If you don't

know what the hockey stick is, do a Google search, including the word

'climate.' You'll learn that it is the nickname for a remarkable graph that has

become a poster child for the environmental movement. Published by M. Mann and

colleagues in 1998 and 1999, the plot showed that the climate of the Northern

Hemisphere had been remarkably constant for 900 years until it suddenly began

to heat up about 100 years ago—right about the time that human use of

fossil fuels began to push up levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. The overall

shape of the curve resembled a hockey stick laying on its back—a straight

part with a sudden bend upwards near the end.

The hockey stick

was turned from a scientific plot into the most widely reproduced picture of

the global warming discussion. The version below comes from the influential

2001 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The hockey

stick figure appears five times in just the summary volume alone.

The 'hockey stick'

(from the IPCC 2001 report)

Soon the graph

acquired a very effective sound bite: 1998 was the warmest year in the last

thousand years. This carried a compelling conclusion: global warming is real;

humans are to blame; we must do something—hurry and ratify the Kyoto

treaty on limitations of fossil fuel emissions. Yet some scientists urged

caution, a go slow approach. As a wise man once warned, 'do not let the merely

urgent interfere with the truly important.'

There was a

minor scientific glitch. The hockey stick contradicted previous work that had

concluded that there had been a 'medieval warm period.' In fact, it disagreed

with a plot published by the IPCC itself a decade earlier (in its 1990 report)

that showed pronounced warm temperatures from the years 1000 to 1400.

Such

inconsistencies are common in science, and scientists love them. They mean more

work, maybe a little public attention (which can't hurt funding), and the

excitement that comes with the effort to resolve uncertainty. The Soon and

Baliunas paper was part of this process. Their paper presented all the data in

favor of the medieval warm period.

The debate grew.

Critics of Soon and Baliunas charged that their paper wasn't balanced; because

it consisted of a compilation of data showing warming at different locations at

different times, the criticism went, the work was not a valid refutation of the

hockey stick analysis, which had combined a much larger set of data. That

was a valid concern, but it didn't necessarily mean that the Soon and Baliunas

results should be ignored. It simply meant that the issue was still open.

Meanwhile,

critics excoriated Climate Research for allegedly failing to vet the Soon and

Baliunas paper properly. The publisher, a German company called Inter-Research,

agreed, leading to the resignation of the journal's editor-in-chief and,

eventually, five other editors.

Then last month

the situation became even more complex. S. McIntyre and R. McKitrick published

a paper in Energy and Environment with a detailed critique of the original

hockey stick work. They stated bluntly that the original Mann papers contained

'collation errors, unjustifiable truncations of extrapolation of source data,

obsolete data, geographical location errors, incorrect calculations of

principal components, and other quality control defects.' Moreover, when they

corrected these errors, the medieval warm period came back—strongly.

Mann, et al., disagreed. They immediately posted a reply on the Web, with their

criticism of McIntyre and McKitrick's analysis.

The disagreement

is not political; most of it arises from valid issues involving physics and

mathematics. First the physics. An accurate thermometer wasn't invented until 1724

(by Fahrenheit), and good worldwide records didn't exist prior to the 1900s.

For earlier eras, we depend on indirect estimates called proxies. These include

the widths of tree rings, the ratio of oxygen isotopes in glacial ice,

variations in species of microscopic animals trapped in sediment (different

kinds thrive at different temperatures), and even historical records of harbor

closures from ice. Of course, these proxies also respond to other elements of

weather, such as rainfall, cloud cover, and storm patterns. Moreover, most

proxies are sensitive to local conditions, and extrapolating to global climate

can be hazardous. Chose the wrong proxies and you'll get the wrong answer.

The math

questions involve the procedures for combining data sets. Mann used a

well-known approach called principle component analysis. This method extracts

from a set of proxy records the behavior that they have in common. It can be

more sensitive than simply averaging data, since it typically suppresses

nonglobal variations that appear in only a few records. But to use it, the

proxy records must be sampled at the same times and have the same length. The

data available to Mann and his colleagues weren't, so they had to be averaged,

interpolated, and extrapolated. That required subjective judgments

which—unfortunately—could have biased the conclusions.

When I first

read the Mann papers in 1998, I was disappointed that they did not discuss such

systematic biases in much detail, particularly since their conclusions repealed

the medieval warm period. In most fields of science, researchers who express

the most self-doubt and who understate their conclusions are the ones that are

most respected. Scientists regard with disdain those who play their conclusions

to the press. I was worried about the hockey stick from the beginning.

When I wrote my book on paleoclimate (published in 2000), I initially included

the hockey stick graph in the introductory chapter. In the second

draft, I cut the figure, although I left a reference. I didn't trust it

enough.

Last month's

article by McIntyre and McKitrick raised pertinent questions. They had been

given access (by Mann) to details of the work that were not publicly available.

Independent analysis and (when possible) independent data sets are ultimately

the arbiter of truth. This is precisely the way that science should, and

usually does, proceed. That's why Nobel Prizes are often awarded one to three

decades after the work was completed—to avoid mistakes. Truth is not easy

to find, but a slow process is the only one that works reliably.

It was

unfortunate that many scientists endorsed the hockey stick before it could be

subjected to the tedious review of time. Ironically, it appears that these

scientists skipped the vetting precisely because the results were so important.

Let me be clear.

My own reading of the literature and study of paleoclimate suggests strongly

that carbon dioxide from burning of fossil fuels will prove to be the greatest

pollutant of human history. It is likely to have severe and detrimental effects

on global climate. I would love to believe that the results of Mann et al. are

correct, and that the last few years have been the warmest in a millennium.

Love to believe?

My own words make me shudder. They trigger my scientist's instinct for caution.

When a conclusion is attractive, I am tempted to lower my standards, to do

shoddy work. But that is not the way to truth. When the conclusions are

attractive, we must be extra cautious.

The public

debate does not make that easy. Political journalists have jumped in, with

discussion not only of the science, but of the political backgrounds of the

scientists and their potential biases from funding sources. Scientists

themselves are also at fault. Some are finding fame and glory, and even a sense

that they are important. (That's remarkably rare in science.) We drift into ad

hominem counterattacks. Criticize the hockey stick and some colleagues seem to

think you have a political agenda—I've discovered this myself. Accept

the hockey stick, and others accuse you of uncritical thought.

There are also

the valid concerns of politicians who have to make decisions in a timely way.

In 1947, Harry Truman grew so annoyed at the prevarications of economists that

he joked that he wanted a one-armed advisor—who could not hedge his

conclusions with the phrase 'on the other hand.'

Some people

think that science is served by open debate between left-handed and

right-handed advocates, just as in politics. But the history of science shows

it is best done by people who have two hands each. Present results with

caution, and insist on equivocating. Leave it to the president and his advisors

to make decisions based on uncertain conclusions. Don't exaggerate the results.

Use both hands. We cannot afford to lower our standards merely because the

problem is so urgent.

--------------------------------------

Richard A.

Muller, a 1982 MacArthur Fellow, is a physics professor at the University of

California, Berkeley, where he teaches a course called 'Physics for Future

Presidents.' Since 1972, he has been a Jason consultant on U.S. national

security.